The Current State of Forest Protection

Only 8 of the top 20 countries with the highest rate of tropical deforestation have quantified targets on forests in their national climate action plans. This is an alarming statistic.

The private sector's financial contribution to combating deforestation through forest carbon credits has faced significant drawbacks, largely due to the lack of proven additionality in reforestation and afforestation projects. Additionality is defined as greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reductions that would not have occurred without the project. In simple terms, some projects claim to store tonnes of CO₂ within a 30-year period, but their predictions are either too optimistic or flawed because the absorption of carbon would have happened anyway without the said project. Issues such as faulty deforestation baselines, leakage, and shifts in land management—including policy changes—have eroded credibility.

By design, individual forest carbon credit projects are highly vulnerable to reversibility (when forests are disturbed or destroyed in the future releasing the “stored carbon”) because they operate within small, defined areas of forest. The bottom line? Traditional forest carbon credit projects are too risky to be the game-changer we need.

A Paradigm Shift: Carbon credits issued by countries

Halting and reversing deforestation and forest degradation on a large scale usually requires actions that only governments can perform, but they, like the private sector, need incentives.

This is why a new model—jurisdictional carbon credits—was set up and gained traction at COP28. Under Articles 6.2 and 6.4 of the Paris Agreement, countries can now issue credits. Instead of focusing on small parcels of land, this approach treats all forested areas within a region as a single unit. These credits allow countries to sell carbon credits on the voluntary market, scaling up the approach to forest conservation. Jurisdictional credits require that all forested areas within a national or subnational jurisdiction be considered as the baseline. This approach enhances integrity, secures increased funding, and promotes broader public policy interventions. The deforestation baseline uses the average deforestation rate of the past 10 years within a given jurisdiction. This means the baseline can be re-evaluated regularly.

Jurisdictional projects could generate six times more carbon credits than current models by 2030. One example of those jurisdictional projects is the Singapore-Ghana implementation agreement.

Eventually, all individual carbon credit schemes will link site-level forest conservation and country/province goals to align with jurisdictional credits, and it will reduce the risk of over-crediting.

Towards a forest risk impact tool

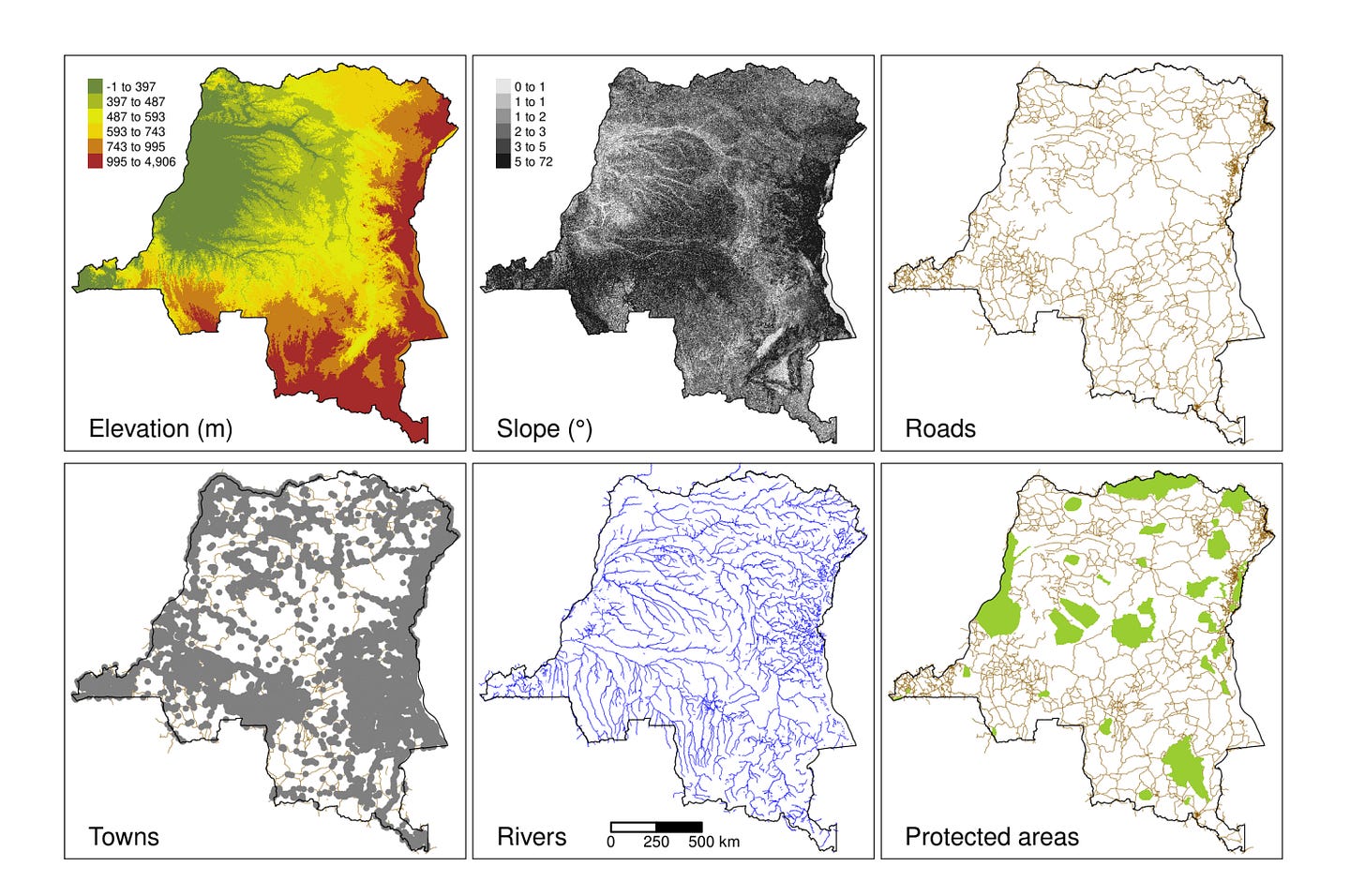

A new open-source tool, Deforisk, identifies areas with high risks of deforestation. It aims to improve countries land use policies and support their strategies at combating deforestation. Deforisk maps deforestation risks at high resolution, factoring in different variables that can now be evaluated concurrently, combining multiple decision trees to create a robust and accurate predictive model.

· Forest accessibility (distance to roads and towns, protected area status, elevation)

· Land tenure (ownership structures that influence land-use changes)

· Moisture levels (key for predicting fire risks)

Let’s look at some of the variables that affect deforestation.

Threats to Forests

Forest edge expansion. A recent study found that forest edge area increased from 27 to 31% of the total forest area in just 10 years, with the largest increase in Africa. By 2100, 50% of tropical forest area will be at the forest edge, causing additional carbon emissions of up to 500 million MT carbon per year.

Efforts to limit fragmentation in the world’s tropical forests are important for climate change mitigation. Forest fragmentation also intensifies biodiversity loss, tree mortality, and fire risk, particularly as wind and drought stress penetrate several hundred meters into forests from the edge.

Hydroclimate whiplash. The “expanding atmospheric sponge,” is the atmosphere’s ability to evaporate, absorb and release 7% more water for every degree Celsius the planet warms.

Whiplash involves rapid swings between intensely wet weather—which results in extensive bush growing—followed by dangerously dry weather—which causes the bush to dry and become very flammable, fuelling wildfires. This "hydroclimate whiplash" has played a major role in intensifying wildfires, including those in Los Angeles in early 2025.

Hidden dangers of revegetation and monoculture. There is a growing awareness that monoculture tree plantations are exacerbating the risk of deforestation. The 2023 Canadian wildfires demonstrated the dangers of monoculture forests, which are often highly flammable.

Right now, 50% of forest carbon credits come from fast-growing tree plantations, mostly pine, eucalyptus, and China fir. By 2035, pine plantations could dominate 75% of the carbon credit market. That’s a big problem—biodiverse, resilient forests are being replaced with fire-prone tree farms.

In some areas, not replanting trees is the best strategy. In Attica, Greece, where forests have burnt repeatedly in the last 30 years, experts are looking at alternative land uses like vineyards and orchards.

NDCs 3.0 to set forest protection targets

It is time to move from the tunnel vision of carbon credits. Impact should be considered with a systemic lens. This can only be made possible when a country has adopted a national strategy for protecting their forests. As countries prepare to submit their next round of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) for COP30 2025, they must avoid siloed approaches and recognise the interconnectedness of ecosystems.

Brazil’s missed opportunity

Brazil is a great example of what’s possible—and what’s missing. In the last 3 years, they’ve made real progress in reducing deforestation through data-driven monitoring and innovating with new models such as selective logging concessions, but their NDC 3.0 doesn’t commit to zero deforestation by a set deadline. That’s a glaring omission, considering that 80% of Brazil’s net-zero target could be met just by stopping deforestation and restoring native habitats. The challenge? Conservation competes with powerful mining and bioenergy crop industries. Recent research recorded an increase in deforestation linked to soy, of which Brazil is the leading world exporter.

Until Brazil and other nations integrate long-term forest protection into economic planning, carbon credit markets will continue to fall short.

The road ahead is long. Carbon credits are just one small piece of the puzzle; fortunately, other impact metrics—such as biodiversity protection and sustainable livelihoods—are gaining momentum, helping to drive more climate finance to the right solutions.